You hope it won’t happen: of course you do. We all do. But if, just if, there were a fire at home, then once you’d ensured everyone was safe, what you would rescue?

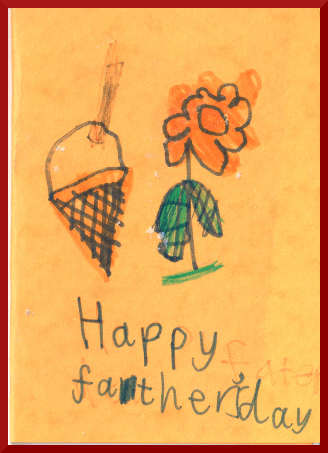

Most of us have something in mind. For me, there’s a pile of birthday cards, Christmas cards, Father’s day cards, drawings, and so on that my daughter has given me. I’m grabbing them. If there’s time, I’ll get the passports too, and there are some other significant and important documents – but only if there’s time.

The passports are replaceable. Yes, it would be a lot of hassle, but in reality I would have all but forgotten about the hassle a year later. Maybe it would be relegated to a dinner party story.

But the cards and drawings that Lucy has given me over the years are irreplaceable. If I lost them, I wouldn’t be joking about it 12 months later.

So what does this have to do with Linux?

It’s about identifying critical data. Irreplaceable data. Data that, when lost, is life-changing – possibly even life-ending – for your business. And this doesn’t just apply to small businesses: we’ve come across some businesses of significant size that haven’t understood this.

There is a deep-rooted and fundamental difference between day to day backups, and backups for disaster recovery.

The day to day backups are there mostly to account for human error, and maybe the odd hardware failure. You accidentally delete a document, or find that all of Appendix A, which you spent almost a day writing last week, has somehow disappeared. That’s OK, you have a backup, so you restore it. If you didn’t have a backup then there would be frustration, irritation, maybe even the odd word that succinctly summarises how you feel. But life, and your business, would go on.

The day to day backups are often stored on site, in the same building as the original data. That’s fine: having them locally means both the backup and any restore are much quicker. Those backups are for convenience, and anything that makes them quicker and more convenient makes sense.

Backups for disaster recovery are a different story. They are there to ensure the survival of the business. If you get to the office tomorrow and see only a smoking crater where your office used to be, it’s the quality of the disaster recovery backups that will play a very significant role in determining whether the business survives.

Disaster recovery backups differ from the day to day backups:

- they must be offsite

- they must prioritise business-critical data

That they must be offsite is, hopefully, self evident. If your office has become a crater, it’s unlikely that much in the way of on-site backups will have survived.

The prioritisation of business-critical data is the part that is often misunderstood, or not even considered. This is the domestic fire equivalent of Lucy’s cards first, then passports, then whatever I can lay my hands on.

Identifying Business-Critical Data

The problem is that if you ask your staff what data is business-critical, a very common answer is “all of it”. That’s an understandable perspective: if some data that they had identified as not being business-critical is lost and there’s no backup, they may well feel that they will be blamed. But, in the same way as not all of the contents of your house are of equal importance, neither is all data truly business-critical. It’s your job to identify that business-critical data.

For a lot of businesses there is significant value in their Intellectual Property (IP). Companies that employ software engineers or developers will want to protect their program code and possibly some regulatory or verification data; for a consultancy it might include textural data such as books, articles, howtos, etc; for an online store, it might include product descriptions and images. This is data that the business depends on.

The next layer might be financial and customer information. Businesses have a legal obligation to keep financial and accounting records, and while the loss of those may not put you out of business, it could certainly spoil your day. Similarly, losing customer records would be at best very embarrassing, but is much more likely to result in lost revenue.

Next might be marketing data, business plans, financial forecasts, staff records and so on. These are (slightly) less critical, but would still represent a major inconvenience and expense if lost.

Of course what comprises business-critical data will vary from business to business: the above is simply an example. Few would argue, however, that keeping an off-site backup of your browser bookmarks is as important as a backup of your Intellectual Property.

Putting It Into Practice

The quantity of data that is truly business-critical will be a very small subset of your overall data. Step one is to identify that data, and ensure it is being backed up off-site at an appropriate interval. You need to check that:

- the correct data is being backed up

- the backup completes within a reasonable time

- there were no errors with the backup

- the last successful backup is recent (for example, within the last 48 hours)

Once the business-critical data is being backup up off-site in this way, you can turn to the next layer down, such as the financial information in the example above. The same criteria apply, and as there is now more data, it will take longer to backup.

As you add more layers, the time taken will increase, and you’ll either reach a point where all data is being backed up in a timely way, or you run out of time. Generally speaking, data backups take place overnight, and it’s helpful for them to have completed (with some margin) before the business day begins. If you run out of time and you still don’t have all your business-critical data backed up, you’ll need to review how it is being backed up to find a faster way (or possibly reconsider what constitutes “business-critical data” for you).

The Test

The final step is to test the backups, and ideally they should be tested by someone who has had no involvement in setting them up. That means clear documentation is needed that doesn’t make assumptions about the reader’s knowledge. Skill level, maybe, but not knowledge: instructions such as “log into the backup system” will need more detail.

Keep a log of test restores from backups, noting when they were done, who did them, and what problems they had. If the person doing the restore cannot complete it without seeking help, the documentation is lacking – and that is very likely to be the case at first.

Could This Article Be Improved?

Let us know in the comments below.